The LVL desk build continued with the legs. I milled 8/4 material, then joined two pieces to form four 3-1/2″-square legs. Square wouldn’t do, so we decided to taper the 28″ lengths over 24-1/2″, leaving a bit of square at the top. Tapering legs is best done at a jointer, if you ask me. As long as you hit your layout lines, you can nail each leg so that they are all tapered exactly. It took only minutes to taper all 16 sides.

The LVL desk build continued with the legs. I milled 8/4 material, then joined two pieces to form four 3-1/2″-square legs. Square wouldn’t do, so we decided to taper the 28″ lengths over 24-1/2″, leaving a bit of square at the top. Tapering legs is best done at a jointer, if you ask me. As long as you hit your layout lines, you can nail each leg so that they are all tapered exactly. It took only minutes to taper all 16 sides.

Still, the legs didn’t have the right look, so we decided to chamfer the corners. But how do you stop the chamfer at the perfect location? You don’t. We trimmed the corners along the legs entire length; that left the square portion at the top end tapering out of the cut made at the router table.

To join the legs to the top, we went with a simple idea – dowels. If we would thought of this at the beginning, we could have drilled the leg ends while the blanks were still square. But, of course, we didn’t, so the set-up was a bit more involved. I rotated the table on my drill press, clamped a straightedge in position then centered the 1-1/4″-diameter bit in the leg, which was clamped to the straightedge. (Told you it was more involved.) Holes were drilled about 1-1/2″ deep because the arm of the press came down onto the rotated table to stop the cut. That wasn’t enough of a hole in my opinion. Afterward, each hole was set another 1-1/2″ in depth, and dowels were glued in.

To join the legs to the top, we went with a simple idea – dowels. If we would thought of this at the beginning, we could have drilled the leg ends while the blanks were still square. But, of course, we didn’t, so the set-up was a bit more involved. I rotated the table on my drill press, clamped a straightedge in position then centered the 1-1/4″-diameter bit in the leg, which was clamped to the straightedge. (Told you it was more involved.) Holes were drilled about 1-1/2″ deep because the arm of the press came down onto the rotated table to stop the cut. That wasn’t enough of a hole in my opinion. Afterward, each hole was set another 1-1/2″ in depth, and dowels were glued in.

For each leg to fit tight and flush with the bottom surface of the tabletop, it was imperative that the 1-1/4″-diameter holes drilled through the top be square to the large flat surface.  There’s no better tool than a router for this work. I don’t, however, have a router bit that diameter, so there was no way to plunge the holes as you would when knocking out adjustable shelf pins. The next idea worked perfectly. drill through the top in the correct location using a smaller diameter drill bit (in this case I used 3/4″), then enlarge the hole using a top-mount pattern bit. All that’s needed is a scrap piece of plywood with a hole drilled exactly to size; that’s easy with the drill bit already in the press.

There’s no better tool than a router for this work. I don’t, however, have a router bit that diameter, so there was no way to plunge the holes as you would when knocking out adjustable shelf pins. The next idea worked perfectly. drill through the top in the correct location using a smaller diameter drill bit (in this case I used 3/4″), then enlarge the hole using a top-mount pattern bit. All that’s needed is a scrap piece of plywood with a hole drilled exactly to size; that’s easy with the drill bit already in the press.

To use the jig, clamp the plywood piece in position on the table’s top over the previously drilled hole, slip the router setup into the hole with the bit’s bearing riding along the plywood cutout and rout a perfect matching-size hole in the top. To get through the entire 2″ of top, we had to remove the plywood and repeat the steps using the trimmed portion of the hole as a guide. Easy, peasy!

To use the jig, clamp the plywood piece in position on the table’s top over the previously drilled hole, slip the router setup into the hole with the bit’s bearing riding along the plywood cutout and rout a perfect matching-size hole in the top. To get through the entire 2″ of top, we had to remove the plywood and repeat the steps using the trimmed portion of the hole as a guide. Easy, peasy!

With the holes drilled and the dowels sawn for wedges, we slipped the legs into the top, spilled a little glue into the sliced dowel then drove walnut wedges to bring everything tight. The final look with the dowels and wedges trimmed look good. Plus, there’s no wobble in the table, especially after the glue dried.

With the holes drilled and the dowels sawn for wedges, we slipped the legs into the top, spilled a little glue into the sliced dowel then drove walnut wedges to bring everything tight. The final look with the dowels and wedges trimmed look good. Plus, there’s no wobble in the table, especially after the glue dried.

Build Something Great!

Glen

I’m running the boards across the back from the bottom up about 50″ just as would be seen on a case piece of furniture. I then plan to turn the upper board so its grain runs vertical. To make the transition, I’m using a tongue-and-groove joint. It’s a bit more work and will need a few additional fasteners (nails I suspect), but I can use short pieces of scrap cut off from other projects. Frugal, huh!

I’m running the boards across the back from the bottom up about 50″ just as would be seen on a case piece of furniture. I then plan to turn the upper board so its grain runs vertical. To make the transition, I’m using a tongue-and-groove joint. It’s a bit more work and will need a few additional fasteners (nails I suspect), but I can use short pieces of scrap cut off from other projects. Frugal, huh! I began at the bottom – the bottom board was cut on only one edge. From there to the 50″ mark (it doesn’t have to be that length, it’s just what I chose based on the number of pieces I had to use and the width of those pieces), I fit and positioned each board. The top board – also shiplapped on one edge – was taken back to the tablesaw for the tongue portion of the transition joint. I then slipped the top horizontal board in place and added a couple of clamps to hold things secure.

I began at the bottom – the bottom board was cut on only one edge. From there to the 50″ mark (it doesn’t have to be that length, it’s just what I chose based on the number of pieces I had to use and the width of those pieces), I fit and positioned each board. The top board – also shiplapped on one edge – was taken back to the tablesaw for the tongue portion of the transition joint. I then slipped the top horizontal board in place and added a couple of clamps to hold things secure.

It’s easy to use, I can set up the miter gauge to be square and once the blade is set to 45°, I can use the same setup for two operations. The photo (at right) shows the setup used to bevel the ends. A sacrificial fence with a cut ran through it after the blade was beveled, makes it easy to locate the box parts to trim. I also added a stop-block to keep the parts from creeping away from the blade as the cut is made. One additional point you should glean from this image is my hand placement. My first inclination was to grab the gauge with my right hand and hold the part with my left. If that happened, my left arm would – at some point in the cut – completely block the blade from my view. That’s not good.

It’s easy to use, I can set up the miter gauge to be square and once the blade is set to 45°, I can use the same setup for two operations. The photo (at right) shows the setup used to bevel the ends. A sacrificial fence with a cut ran through it after the blade was beveled, makes it easy to locate the box parts to trim. I also added a stop-block to keep the parts from creeping away from the blade as the cut is made. One additional point you should glean from this image is my hand placement. My first inclination was to grab the gauge with my right hand and hold the part with my left. If that happened, my left arm would – at some point in the cut – completely block the blade from my view. That’s not good. Using the same table-saw setup but placing the gauge on the opposite side of the saw blade, makes the next step cake. Once again, make a pass over the blade to establish where the cut hits the sacrificial fence to use to align the parts, then position one piece to that kerf. Make sure to dial back the blade height, then clamp a stop-block in position to use as a guide for each cut. Notice how I switched my hand placement for this round of cuts.

Using the same table-saw setup but placing the gauge on the opposite side of the saw blade, makes the next step cake. Once again, make a pass over the blade to establish where the cut hits the sacrificial fence to use to align the parts, then position one piece to that kerf. Make sure to dial back the blade height, then clamp a stop-block in position to use as a guide for each cut. Notice how I switched my hand placement for this round of cuts.

To rabbet the edges to fit into the roughly 1/4″-wide grooves, I use a two-step method at my table saw – what can’t you do with this machine? The process is straightforward. After you get the necessary measurements from the box parts – you can measure the width and length right in the grooves of the front and end – cut the bottom to size (you may want to go a bit less in width to accommodate for any seasonal movement if your box is on the wide side. The first pass is with the bottom face down against the table top – set the blade height to leave a 1/4″ of material after the cut. I make a 3/8″-wide rabbet to make sure the edge doesn’t interfere with the box as it goes together. The next step is to readjust the blade height to just tick the top edge of the previous cut (with the part standing on edge at the fence), and to set the fence to leave the tongue thick enough to slide into the groove. While it doesn’t make much of a difference here, it’s good practice to run the end-grain cuts first.

To rabbet the edges to fit into the roughly 1/4″-wide grooves, I use a two-step method at my table saw – what can’t you do with this machine? The process is straightforward. After you get the necessary measurements from the box parts – you can measure the width and length right in the grooves of the front and end – cut the bottom to size (you may want to go a bit less in width to accommodate for any seasonal movement if your box is on the wide side. The first pass is with the bottom face down against the table top – set the blade height to leave a 1/4″ of material after the cut. I make a 3/8″-wide rabbet to make sure the edge doesn’t interfere with the box as it goes together. The next step is to readjust the blade height to just tick the top edge of the previous cut (with the part standing on edge at the fence), and to set the fence to leave the tongue thick enough to slide into the groove. While it doesn’t make much of a difference here, it’s good practice to run the end-grain cuts first.

If you’re using 3/4″-thick material, after the 1/8″ groove you have 5/8″ of thickness remaining. For me this is a bit of work completed at the router table. Set the height of the bit then adjust the fence so its aligned with the router bit exactly at the table’s top edge. This takes advantage of the entire thickness of your blade – if you’re slightly thinner after your cut, that’s OK, but do not leave a flat on the edge of the dovetail. (Notice the solid push block used to guide the tall drawer divider through the cut.) After you have the dovetail ends created, cut away the back edge leaving a 1″-wide dovetail – trim the dovetail away flush with the square shoulder on your blade.

If you’re using 3/4″-thick material, after the 1/8″ groove you have 5/8″ of thickness remaining. For me this is a bit of work completed at the router table. Set the height of the bit then adjust the fence so its aligned with the router bit exactly at the table’s top edge. This takes advantage of the entire thickness of your blade – if you’re slightly thinner after your cut, that’s OK, but do not leave a flat on the edge of the dovetail. (Notice the solid push block used to guide the tall drawer divider through the cut.) After you have the dovetail ends created, cut away the back edge leaving a 1″-wide dovetail – trim the dovetail away flush with the square shoulder on your blade.

It’s time to define the socket. This is where your ability to saw comes into play. Cut the two sides of your layout down to the inch mark. Follow both lines as you saw. After you’ve established the socket’s outer edges, make a few additional saw cuts between the lines – the more kerfs you have, the easier the next couple steps become and the cleaner your socket will be to work.

It’s time to define the socket. This is where your ability to saw comes into play. Cut the two sides of your layout down to the inch mark. Follow both lines as you saw. After you’ve established the socket’s outer edges, make a few additional saw cuts between the lines – the more kerfs you have, the easier the next couple steps become and the cleaner your socket will be to work. You can jam a chisel into the slots, or if they’re thin enough, you can break the pieces out with your fingers. The neat things is that when they break – due to the grain orientation – the slivers break flush with the bottom edge of the socket. (Sometimes they do break slightly above the line.) With the pieces out of the way, pare the socket bottom so it’s smooth and level. Make sure the socket is level from outside to inside. And it wouldn’t hurt to slope a bit toward the inside – that guarantees you’ll have a tight fit on the exterior of your case.

You can jam a chisel into the slots, or if they’re thin enough, you can break the pieces out with your fingers. The neat things is that when they break – due to the grain orientation – the slivers break flush with the bottom edge of the socket. (Sometimes they do break slightly above the line.) With the pieces out of the way, pare the socket bottom so it’s smooth and level. Make sure the socket is level from outside to inside. And it wouldn’t hurt to slope a bit toward the inside – that guarantees you’ll have a tight fit on the exterior of your case. If you’ve sawn to the layout lines and trimmed the socket even at the bottom, your blades should fit easily. Brush glue onto the dovetail and into the socket (the best glue surface is the flat-grain to flat-grain connection at the bottom of the socket), then drive the workpiece home. By the way, don’t forget to repeat these steps twice for each drawer blade or divider. Test-fits are terrible with only one socket cut.

If you’ve sawn to the layout lines and trimmed the socket even at the bottom, your blades should fit easily. Brush glue onto the dovetail and into the socket (the best glue surface is the flat-grain to flat-grain connection at the bottom of the socket), then drive the workpiece home. By the way, don’t forget to repeat these steps twice for each drawer blade or divider. Test-fits are terrible with only one socket cut.

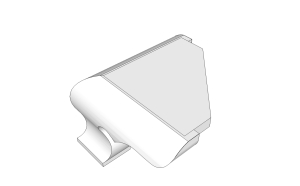

Of course, you would be correct. What really holds the feet to the case are glue blocks. These blocks also carry the bulk of the load of your chest. On the case I’m currently at work on, the thickness of the feet allows about an 1/8″ of the feet to lap onto the case itself. Then, with the glue blocks in place, the weight of the case is divided on the actual feet and on the glue blocks – the vertical block holds the weigh while the two horizontal blocks keep the assembled foot attached.

Of course, you would be correct. What really holds the feet to the case are glue blocks. These blocks also carry the bulk of the load of your chest. On the case I’m currently at work on, the thickness of the feet allows about an 1/8″ of the feet to lap onto the case itself. Then, with the glue blocks in place, the weight of the case is divided on the actual feet and on the glue blocks – the vertical block holds the weigh while the two horizontal blocks keep the assembled foot attached. The SketchUp drawing at the left shows how the plate fits to the feet; a thin bead of glue and brads secure the plate to the feet. The assembled unit is then screwed directly to the case bottom with the unit sticking out in front of the case. The look is completed by wrapping a molding around the case. An example of this type of connection is seen in the opening photo, although you cannot see the plate. That’s by design. As you see in the drawing, the cutout for the plate does not blow through the end of the foot.

The SketchUp drawing at the left shows how the plate fits to the feet; a thin bead of glue and brads secure the plate to the feet. The assembled unit is then screwed directly to the case bottom with the unit sticking out in front of the case. The look is completed by wrapping a molding around the case. An example of this type of connection is seen in the opening photo, although you cannot see the plate. That’s by design. As you see in the drawing, the cutout for the plate does not blow through the end of the foot. I used this method on the Pennsylvania blanket chests in the

I used this method on the Pennsylvania blanket chests in the  Structural dovetails are the best dovetails because these joints can have over-sized tails and pins, and this is where you get the opportunity to either bang out a set without regard to the above mentioned conditions, use alternative methods to cut and fit your joints or practice in an area that will not see the light of day – why practice on a scrap when you can contribute to your project while building your skills. For me, alternative methods of work is my focus.

Structural dovetails are the best dovetails because these joints can have over-sized tails and pins, and this is where you get the opportunity to either bang out a set without regard to the above mentioned conditions, use alternative methods to cut and fit your joints or practice in an area that will not see the light of day – why practice on a scrap when you can contribute to your project while building your skills. For me, alternative methods of work is my focus.