In a blended woodworking shop – how any woodworking shop should be set up – you make choices about when hand work is appropriate and when it makes better sense to use power tools. That decision should not necessarily be guided by a passion for any particular method or tool; as woodworkers, we face this whenever we hope to be productive in our shops.

In a blended woodworking shop – how any woodworking shop should be set up – you make choices about when hand work is appropriate and when it makes better sense to use power tools. That decision should not necessarily be guided by a passion for any particular method or tool; as woodworkers, we face this whenever we hope to be productive in our shops.

In a post a few weeks back (read it here), I wrote about how easy it was to make a simple scratch beader (scratch stock) to profile the arched moldings on the Egerton clock hood. With that project on hold while I build a cover piece for an upcoming issue of Popular Woodworking Magazine, I faced a similar choice as I made drawer molding for the transitional lowboy. (If you’re a furniture purist, don’t tell me I’m not suppose to use the term transitional – that best describes the project on which I’m working.)  The moldings are a double-bead design that signifies later William & Mary period work. And the fact that the lowboy has cabriole legs (Queen Anne) also indicates a transitional build.

The moldings are a double-bead design that signifies later William & Mary period work. And the fact that the lowboy has cabriole legs (Queen Anne) also indicates a transitional build.

I decided to make another simple beader, but this time the tool was a bit more involved. Not only did I drill the holes and sand the profile, I needed to set the blade into a handle to register the molding with each pass. Even with the handle added, making the tool was too easy.

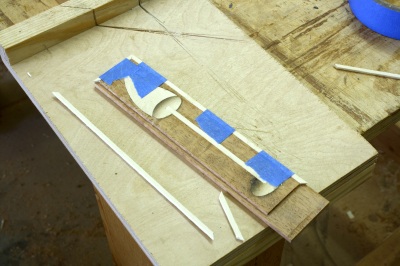

In order to use the scratch beader, I ran a slot down the middle of my stock using a slot cutter setup in my router table. At the bench with the stock set in my vise, I scratched the double-bead profile into the edge. At my table saw, I set the cut for 1/4″ then ripped the first piece of molding free. Everything worked, but the process to get six pieces of molding was too long.

Using my router table with a 1/4″ corner-beading router bit installed, I ran a pass to form the bead, flipped the stock to rout a bead at the opposite face, then ripped the molding at my table saw. I was easily convinced that this was the process I would use. But what guided my decision? First there was the ease of the entire process. Router cut was far easier and quicker than walking through the steps needed to do the work by hand. Also, the pattern or profile was consistent with each piece of molding cut. This is important because there are a couple of places, as you can see in the opening photo, where these molding pieces meet and intersect with one another – matching profiles are easier to fit and blend (hand-cut work can require further shaping and sanding).

Using my router table with a 1/4″ corner-beading router bit installed, I ran a pass to form the bead, flipped the stock to rout a bead at the opposite face, then ripped the molding at my table saw. I was easily convinced that this was the process I would use. But what guided my decision? First there was the ease of the entire process. Router cut was far easier and quicker than walking through the steps needed to do the work by hand. Also, the pattern or profile was consistent with each piece of molding cut. This is important because there are a couple of places, as you can see in the opening photo, where these molding pieces meet and intersect with one another – matching profiles are easier to fit and blend (hand-cut work can require further shaping and sanding).

What did I give up? The original molding profile I was after was a 3/16″ bead at each edge of the 5/8″-wide stock, with a 1/4″ of flat between the two beads. What I made using power tools was a 1/4″ bead at both edges with an 1/8″ flat – not the same design. I could have found and purchased a 3/16″ corner-beading router bit, but I didn’t think it was that important. If this was a customer-purchased lowboy, I would have built the piece with the 3/16″ beads. But given the fact that it is a piece for me – as most of the projects you build are for you – I opted to be more productive in my shop.

Build Something Great!

Glen