Most everyone looks forward to Friday, but this past Friday was especially fun. The Wednesday before was not so much fun – it was filled with wood dust, wood chips and lumber stacking, but not in a good way. Wednesday evening I spent cleaning my shop and rearranging the tools for a visit from Charles Brock, the Highland Woodworker.

Most everyone looks forward to Friday, but this past Friday was especially fun. The Wednesday before was not so much fun – it was filled with wood dust, wood chips and lumber stacking, but not in a good way. Wednesday evening I spent cleaning my shop and rearranging the tools for a visit from Charles Brock, the Highland Woodworker.

Chuck and his business partner Steve began their Friday at the American Woodworker and Popular Woodworking Magazine shop in Blue Ash, Ohio, filming clips for upcoming episodes of The Highland Woodworker, which is Web TV for Woodworkers. (If you aren’t familiar with Chuck’s online show, you should sit a spell and take in a few episodes when you have some free time.)

Later in the afternoon, we drove to my shop where we filmed a short interview section in which I discuss some of my early woodworking adventures, talked about what I find relevant in woodworking and I even shared a couple of stories about my (and my Dad’s) early days with Popwood. From there we talked about jointers and jointer setup, and we spent a few minutes discussing aniline dyes in finishing – you have to make the tiger-maple curls “pop.”

Later in the afternoon, we drove to my shop where we filmed a short interview section in which I discuss some of my early woodworking adventures, talked about what I find relevant in woodworking and I even shared a couple of stories about my (and my Dad’s) early days with Popwood. From there we talked about jointers and jointer setup, and we spent a few minutes discussing aniline dyes in finishing – you have to make the tiger-maple curls “pop.”

All this film work will end up on The Highland Woodworker later in the year. And when I get an exact date, I’ll be sure to let you know. Until then, below is the current episode for you to watch. If you slide about 15 minutes into the episode, you’ll find a guy who looks a lot like me talking to Chuck about shellac, but do watch the rest of the show. There’s some great woodworking information to be found, and best of all, it’s entertaining, too.

Build Something Great!

Glen

to the bit to guide it path – no pilot (that’s a throw-back design) or bearing such as what we have on most roundover bits. In the right-hand photo you can see the difference between the two different bits that basically cut the same profiles. Both router bits shown have a 1/4″ roundover profile. (Click the photo to enlarge the image.)

to the bit to guide it path – no pilot (that’s a throw-back design) or bearing such as what we have on most roundover bits. In the right-hand photo you can see the difference between the two different bits that basically cut the same profiles. Both router bits shown have a 1/4″ roundover profile. (Click the photo to enlarge the image.)

Of course, you would be correct. What really holds the feet to the case are glue blocks. These blocks also carry the bulk of the load of your chest. On the case I’m currently at work on, the thickness of the feet allows about an 1/8″ of the feet to lap onto the case itself. Then, with the glue blocks in place, the weight of the case is divided on the actual feet and on the glue blocks – the vertical block holds the weigh while the two horizontal blocks keep the assembled foot attached.

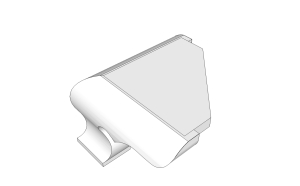

Of course, you would be correct. What really holds the feet to the case are glue blocks. These blocks also carry the bulk of the load of your chest. On the case I’m currently at work on, the thickness of the feet allows about an 1/8″ of the feet to lap onto the case itself. Then, with the glue blocks in place, the weight of the case is divided on the actual feet and on the glue blocks – the vertical block holds the weigh while the two horizontal blocks keep the assembled foot attached. The SketchUp drawing at the left shows how the plate fits to the feet; a thin bead of glue and brads secure the plate to the feet. The assembled unit is then screwed directly to the case bottom with the unit sticking out in front of the case. The look is completed by wrapping a molding around the case. An example of this type of connection is seen in the opening photo, although you cannot see the plate. That’s by design. As you see in the drawing, the cutout for the plate does not blow through the end of the foot.

The SketchUp drawing at the left shows how the plate fits to the feet; a thin bead of glue and brads secure the plate to the feet. The assembled unit is then screwed directly to the case bottom with the unit sticking out in front of the case. The look is completed by wrapping a molding around the case. An example of this type of connection is seen in the opening photo, although you cannot see the plate. That’s by design. As you see in the drawing, the cutout for the plate does not blow through the end of the foot. I used this method on the Pennsylvania blanket chests in the

I used this method on the Pennsylvania blanket chests in the