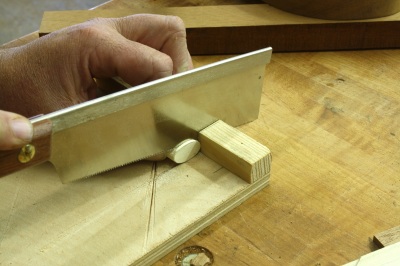

In woodworking, one of the most satisfying things is that you never know it all. Everyday there is something knew to learn. That’s one of the things that keeps me looking and listening and trying new ideas. In the left-hand photo, you see how I’ve set up to bend stringing since I first began working with the material. I grabbed a length of pipe in Vise-grips, clamped it into my bench vise, heated the pipe and bent the stringing over the pipe using a metal-strap backer. If you look close, you see a nail set slipped between the grips and vise. I sometimes found that downward pressure as the bend was taking place could cause the setup to move in the vise, and that’s not a good thing to have happen. The nail set stopped that.

In woodworking, one of the most satisfying things is that you never know it all. Everyday there is something knew to learn. That’s one of the things that keeps me looking and listening and trying new ideas. In the left-hand photo, you see how I’ve set up to bend stringing since I first began working with the material. I grabbed a length of pipe in Vise-grips, clamped it into my bench vise, heated the pipe and bent the stringing over the pipe using a metal-strap backer. If you look close, you see a nail set slipped between the grips and vise. I sometimes found that downward pressure as the bend was taking place could cause the setup to move in the vise, and that’s not a good thing to have happen. The nail set stopped that.

As I’ve demonstrated this technique to different woodworking groups, I’ve had occasion to see a few interesting string-bending setups, including a massive three-pipe selection that bolted to a workbench and allowed a constant flame to keep the pipe at the correct temperature for bending – whatever that is. I’ve also been asked so many times about using a heating iron as does Steve Latta; sorry Steve, that’s way too slow.

I did, however, learn a new setup while teaching my session at Woodworking in America this past weekend (the reason there was no post on this blog last Sunday). I traveled to Winston-Salem, N.C. without my Vise-grips and nail set. When it came time to demonstrate the technique, I was at a loss. Until, that is, I grabbed the F-style clamp I tossed in the conglomerate of stuff I’d taken along. With the length of pipe secure in the clamp, I set it into the bench vise with the handle resting against the top of the vise. No amount of downward force would cause the setup to move. And as long as you remove any plastic fittings from the clamp, heat from my torch was not a worry. It worked great.

There’s always something new to learn in woodworking.

There’s always something new to learn in woodworking.

Build Something Great!

Glen