Something that I preach is that we woodworkers should use the best tool for the job. It that’s a table saw, jointer or big-honkin router, so be it. It the best tool is a handplane, egg-beater drill or sharp chisel, go for it.  To be wholly dedicated to one woodworking discipline while ruling out others is nuts.

To be wholly dedicated to one woodworking discipline while ruling out others is nuts.

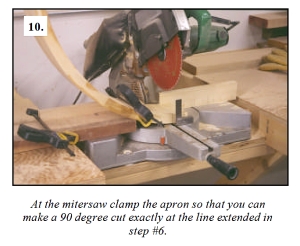

The story I like to tell is a tale on myself. When I built the Baltimore Card Table article for Popular Woodworking Magazine, I was more dedicated to power tools even though I used hand tools. In one of the early steps of the build, I needed to trim the ends of the brick-laid apron. I spent 20 minutes or more setting up the cut at my miter saw. Of course, the cut was square and right. (See the image from the article above.)

Years later, after hand tools began to play a bigger role in my day-to-day woodworking, I taught how to build that table at a woodworking school. When the time came to trim the apron, I grabbed my pencil and square, laid in the lines then made the cut using a hand saw. Of course, the cut was square and right. The difference was that I did not spend 20 minutes setting up the cut.

What’s important is to choose and use the best tool for the job.

In the photo below, I guess the tool would be classified as a hand tool. I know, however, that it is the best tool for the job. Why? No only does this tool make spreading the oil/varnish mix quick to accomplish and easier to direct finish were it’s needed, the process also warms the oil ever so slightly to better allow mixture to soak into the surface.

Build Something Great!

Glen

I’m running the boards across the back from the bottom up about 50″ just as would be seen on a case piece of furniture. I then plan to turn the upper board so its grain runs vertical. To make the transition, I’m using a tongue-and-groove joint. It’s a bit more work and will need a few additional fasteners (nails I suspect), but I can use short pieces of scrap cut off from other projects. Frugal, huh!

I’m running the boards across the back from the bottom up about 50″ just as would be seen on a case piece of furniture. I then plan to turn the upper board so its grain runs vertical. To make the transition, I’m using a tongue-and-groove joint. It’s a bit more work and will need a few additional fasteners (nails I suspect), but I can use short pieces of scrap cut off from other projects. Frugal, huh! I began at the bottom – the bottom board was cut on only one edge. From there to the 50″ mark (it doesn’t have to be that length, it’s just what I chose based on the number of pieces I had to use and the width of those pieces), I fit and positioned each board. The top board – also shiplapped on one edge – was taken back to the tablesaw for the tongue portion of the transition joint. I then slipped the top horizontal board in place and added a couple of clamps to hold things secure.

I began at the bottom – the bottom board was cut on only one edge. From there to the 50″ mark (it doesn’t have to be that length, it’s just what I chose based on the number of pieces I had to use and the width of those pieces), I fit and positioned each board. The top board – also shiplapped on one edge – was taken back to the tablesaw for the tongue portion of the transition joint. I then slipped the top horizontal board in place and added a couple of clamps to hold things secure.